By Elly Knight, PhD Candidate, University of Alberta and Stu Mackenzie, Director, Migration Ecology, Birds Canada

The Common Nighthawk is one of the Western Hemisphere’s most widespread migratory birds, breeding from coast to coast, and from the Yukon all the way down to Panama. Yet, we know surprisingly little about them, especially their lives after they leave their breeding sites.

So, where do all the Common Nighthawks go? This question has a double meaning: first, where do they go when they’re not breeding; and second, where are they going, as in “Why are they disappearing?”. There is a widespread decline of this species across its range. Common Nighthawks are estimated to have declined by over 50% in the past 40 years. Nighthawks are aerial insectivores – birds that catch insects in flight – which are declining faster than any other group of bird species in Canada.

Common Nighthawk photos: Steven Van Wilgenburg

Our new paper just published in Ecography provides answers to both these questions. A collaboration of organizations across North America, including Birds Canada, deployed new miniaturized GPS-satellite tags on birds at 13 locations across the Common Nighthawk breeding range to understand where these birds spend their time throughout the year. The study was initiated by the Migratory Connectivity Project at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, and co-led with Environment and Climate Change Canada and the University of Alberta.

Photo: Stu Mackenzie

Photo: Emily Upham-Mills

So where do all the nighthawks go? Well, it turns out the final destination for all the populations we tracked is the Amazon and Cerrado biomes of South America, mostly in Brazil. This wasn’t a total surprise, as it is the same wintering region revealed by a preliminary study we published in 2018 that tracked just one population from northern Alberta. What was more surprising was how they got there. All of the nighthawks we tracked from across North America congregated along the Mississippi flyway in the mid-west U.S. before taking a single route across the Gulf of Mexico and down into South America. In fact, this draw towards a single migration route was so strong that one individual from Sydney Island off the coast of British Columbia flew 3000 km due east over the Rockies before beginning its southward journey with the rest of the species. In the spring, individuals headed north, taking a more direct path back to their breeding territories.

Source: Elly Knight

While the details of their travels are fascinating, one could argue that the second “where are they going?” question is the more important one. What is happening to Common Nighthawk populations? We can’t fully answer this question yet, but our study begins to narrow it down.

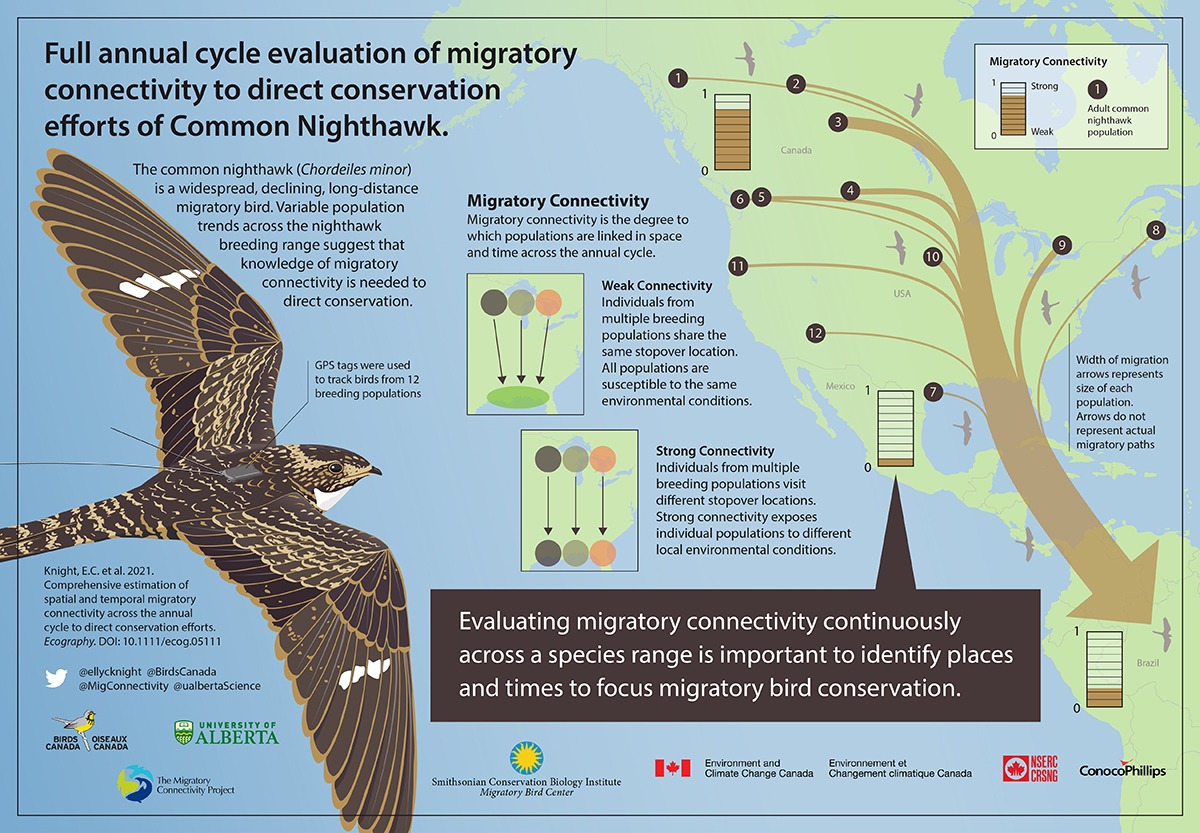

An important first step in the conservation of migratory birds is understanding their migratory connectivity, which is the degree to which birds from a particular population stick together throughout the year. Understanding migratory connectivity is crucial for migratory species conservation because it allows us to begin to determine places and times of year where threats to populations are likely occurring. We used nighthawk data to develop a novel comprehensive approach to understanding of migratory connectivity, both in space and time.

We observed an increase in migratory connectivity (i.e., individuals from populations staying together throughout the year) during the breeding season, during migration in North America, and on spring migration prior to crossing the Gulf of Mexico. We saw weaker migratory connectivity at other times of the year (i.e., individuals from different breeding populations mixing with one another). These differences may help us to understand why different populations of nighthawks are showing different trends; our next step is to delve into this regional variation in population declines and understand more about regional movements.

You can find more interesting information on the regional movements of Common Nighthawks at the Motus Wildlife Tracking System website, Motus.org. And stay tuned for the next installment of exciting nighthawk research!

Wintering sites for different breeding populations Source: Elly Knight

In the meantime, there are plenty of conservation actions we can take to help nighthawks now! Birds Canada’s recently published roadmap to rescuing aerial insectivores outlines a range of “no-regret” actions that we can take now to have positive benefits for biodiversity, including the Common Nighthawk. Birds Canada is working with experts across Canada towards implementation of this roadmap. You can help with Common Nighthawk conservation by adopting a survey route for Birds Canada’s Canadian Nightjar Survey. Surveying for Common Nighthawks on the breeding grounds in June and July is particularly important because migratory connectivity suggests this is where threats to populations could be occurring. The more information we have from the breeding grounds, the better we can evaluate and understand threats to this enigmatic species.